Git merge, git rebase, and crawling out of the git hole

I've crawled enough times out of the git hole so you don't have to. Here's how it works.

To master git is like being a time wizard ✨. You can move across points in time, flying like a bird from one commit to the next, always having a stepping point to go back to when you fuck up. Because let’s be honest, at one point or another, we will.

And that's how we get into the git hole. For those of you lucky enough to have never experienced it, the git hole is that dark place in a developer’s life when your timeline becomes a blur and you’re not sure what happened or where you lost your perfectly-working code.

So what's this big fuss between git merge and git rebase?

The most important thing to understand is that when we’re talking about merging and rebasing, it’s all about how your branch ends where it ends.

What do I mean by this?

What they have in common

git merge and git rebase both join your code with another branch, usually your remote’s master branch.

Where they differ

git merge

When you’re doing a merge, your git tree is coming full circle and you can see this graphically if you download a visual tool like Sourcetree. This means that:

- The branch you’re currently working on, with all your commits and lines of code, will be joined back into master, leaving a trail of where it first left and when you came back into the code.

- Once the conflicts are fixed, if any, it will generate an additional merge commit to keep track of where you were when your code joined master’s.

git rebase

When you rebase, you’re basically playing with time. The result is as if you were coding from and into masters the whole time, except you were really coding off of your own branch. If you look at your tree after a git rebase, it doesn’t have any branches connected back into master because git rebase pretends as if you were "always" coding in master.

This means that when fixing conflicts, rebasing chooses your remote master version as the Queen of All Truth 👸🏻. It’s as if you’re changing the base of your code to be the base of the code found in your masters branch and it does not leave a merging commit because it acts as if it had been “there the whole time”.

Going deeper

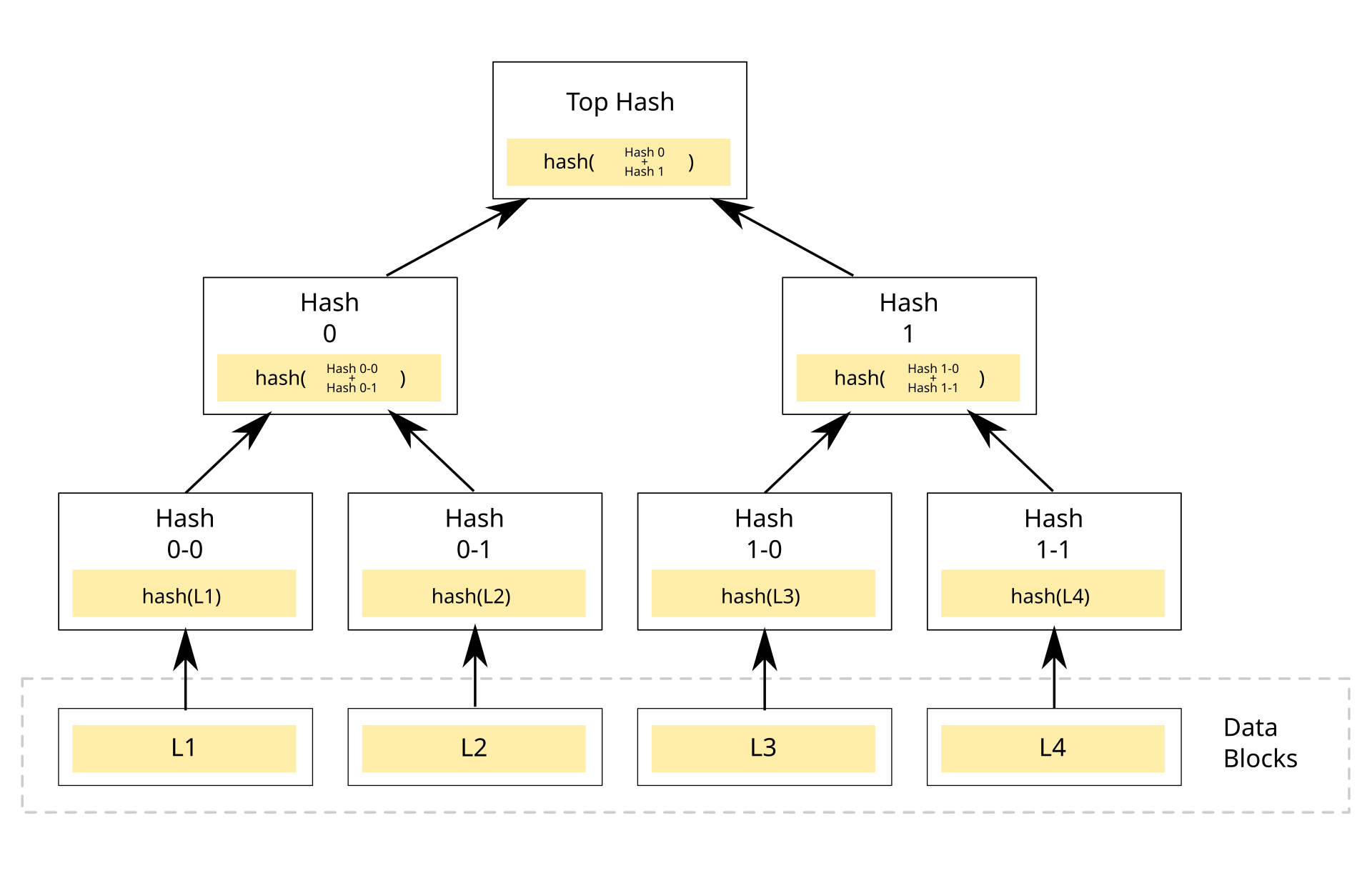

Now, to my understanding, git’s superpower is keeping track of where we are at any given point thanks to us writing commits that mark specific moments to go back to if needed.

So, in my brain, I’ve never really understood why people would want to rebase and play git kong-fu rather than just merge and be on the safe of history. Playing with time like this had to be either contradictory or brilliant.

Indeed, what I hadn’t understood was that the reason why people use rebase instead of merging. Rebasing allows your codebase to be slimmer and have a cleaner overall history without any branches coming off of your linear tree.

With bothgit rebaseandgit merge, you can squash all your commits into one so that your codebase has only one commit per feature, butgit mergewill always produce that final merge commit that only fattens your code and provides no additional value.

And it makes sense. If you have 30+ developers working on the same code, and each is committing every step of their process, you will quickly have a fat and dirty codebase filled with random commits like 'fixed typo'. If you rebase and squash all your commits together, however, the result is a linear tree detailing every feature built and their code.

In practice

Setup

I’ll first create a random index.rb file and make sure git is initiated. This assumes you already have git in your computer connected to a remote repository somewhere. I’ll also create a branch for my first feature.

# Create file

mkdir music-app && touch index.rb

# Initiate git

cd music-app && git init

# Creates github repo with the name of the folder (I’m in using the [hub gem](https://hub.github.com/))

hub create

# Checkout of master and create a branch called bands4tonight

git checkout -b bands4tonight

What we'll build?

I will create a small Ruby app that iterates over an array of my favorite bands and throws at me one by random.

bands = ['Incubus', 'Arctic Monkeys', 'Papooz', 'L’imperatrice', 'Poolside']

puts bands.sample

I then go to the terminal to save up my progress. God forbid I lose my beautiful work.

# Check everything is as I expect

git status

# Adds everything to the bucket

git add .

# Commit my changes

git commit -m 'program returns a sample band'

# Push my code to bands4tonight branch

git push origin bands4tonight

git kong-fu

At this point my code is found remotely in my branch. Great.

Meanwhile, let's say other developers are coding away features on different parts of the app, adding their favorite bands to the mix or just building new functionalities. I need to make sure I have the latest updated version of the code.

# Move to master branch

git checkout master

# Pull in locally the work the other devs have been doing

git pull

# Move into my working branch

git checkout bands4tonight

# Make sure the code I just pulled in is now the base for my working code in my branch

git rebase master

Up until here, my working branch has the latest code from master and acts as if I was always there. Yes, that's exactly what we wanted!

The real trick happens as I keep on adding more code to my feature.

Let's say this week I’m obsessed with a new band (which I'd recommend checking out btw 😉). So I go back into index.rb and add it to my list.

bands = ['Incubus', 'Arctic Monkeys', 'Papooz', 'L’imperatrice', 'Poolside', 'Señor Loop']

Back in terminal, it's time to push my code to my remote branch to make the Pull Request.

git status

git add .

git commit --amend -m 'program returns a sample band'

git push -force

By writing git commit --amend -m ‘..’, I’m adding my new work on top of my latest commit and just moving it forward in the timeline.

This is great because:

1) It conveniently preserves the older versions inside my commit so I can go back in time if I need it.

2) It creates one commit per feature so that someone checking out the code base later on can easily see all the code where one feature is built.

3) It doesn't fatten the codebase with lots of commits, but rather only shows up the one where all code is seen together

4) It doesn't generate an extra merging commit it actually doesn't need.

Also important to note is that because I updated the commit, I am playing wizard with git's regular timeline. This means I have to force the push otherwise git won't allow it.

(Disclaimer here: I was afraid of forcing the push the first time I did it too. But a smart dev told me that at the end of the day, I was only working in my own local branch anyways so allll shall be fine under the Tuscan sun.)

And just like that, once our Pull Request is merged into master, you can run git log and see the clean, elegant timeline we've just created without any unnecessary merge commits.

Because at the end, your git tree is the only tree that is better off without leaves or branches. 🌳

.svg)